A Cabin in the Woods

Guy Saddy, BC Business, June 2019

From Vancouver Island to the Okanagan, sales of vacation home appear to be enjoying a resurgence in BC. If you’re in the market for that perfect getaway, here’s what you need to know.

Surrounded by snow-covered evergreens and almost glowing from the reflected light of the setting sun, the gleaming white cottage looks as if it emerged organically from its setting. The place definitely has character: its bones are classic, enduring. According to the new owner, it’s “a cute little house”, but it’s more than that.

As the sun sinks to the horizon, a toddler, still a bit unsteady on one-year-old legs runs towards the lakeshore.

“Water!” he shouts, as loud as he can. “Water, water, water!”

His parents, Kate MacLennan, global editorial manager for Vancouver-based Lululemon Athletica, and her husband, graphic designer Alex Harvey-Wickens, look on, smiling. In that moment they truly know that their decision to buy a vacation property was the right one.

MacLennan and Harvey-Wickens are part of the growing number of British Columbians who are investing in what was once arguably they ultimate Canadian middle-class dream. A log cabin with a pot-bellied stove located on the edge of a pristine lake, or if you came of age in the early 1970’s, a modernist A-frame with a loft style sleeping area and a ceiling mounted fireplace. From Ontario’s cottage country to the shores of Okanagan Lake, having a place in the wilderness away from it all seemed an almost quintessentially Canadian aspiration, like wanting to play left wing for the Habs, or sharing a case of Moosehead with Stompin’ Tom Connors.

But, for a time, that dream was in danger of being relegated to another era. “In my younger days, people wanted a ‘cabin on the lake’ Then, all of a sudden that desire went away,” says Rudy Nielsen, head of New-Westminster based NIHO Land & Cattle Co., which specializes in brokering BC recreational property sales.

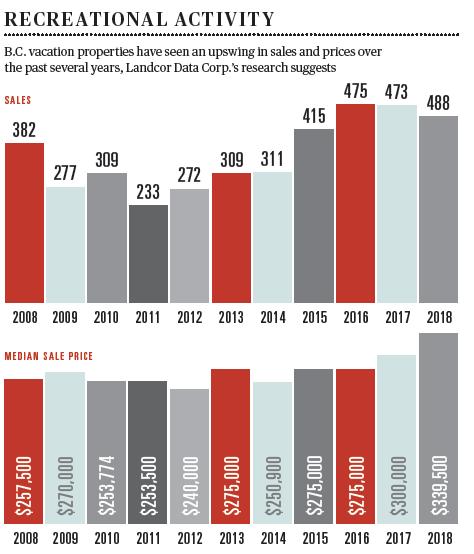

Owning a recreational property fell out of fashion for almost 25 years, Nielsen notes. “And now it’s come back again,” he says. “All of a sudden, people are like, You know, it’s nice to have a cabin on the lake.” Nielsen should know. As president of Landcor Data Corp., he works with BC Assessment to track the sale of all properties in the province. “I’ve been in the real estate business in British Columbia for 50 years,” Nielsen says. “And this is one of the best years yet for people buying recreational property.”

Why the uptick in interest? For some, the cost of home ownership in one of the province’s major urban centres is prohibitive. For others, it’s a stress-relieving escape from a fast-paced life and career, as critical to mental health as, say, a 10-minute morning meditation or a bit of Xanax. For yet another group of buyers, it’s part of their retirement strategy: sell the family home, pocket some coin, and downsize into a lakeside cottage.

The desire for a simpler and safer time spent outdoors is the motivation in those who see value in giving their kids what they, as children, took for granted: an ability to experience nature firsthand, to roam widely and freely. This scenario, to a degree, is what motivated MacLennan. “This would be a place where I could see a lot of stars at night, and where my son is going to discover what it’s like to collect snails,” she says.

The words spill quickly out of MacLennan, 43, a composed communications professional whose approach to buying a vacation property was reflective of MacLennan herself: informed and highly organized. In keeping with her methodical nature, she had a wish list, literally, of what they were looking for, broken down into must-haves, nice-to-haves, and deal breakers.

“Well, it had to have character,” MacLennan says. “We wanted it to be waterfront. Not ‘water view’, waterfront. And a fireplace.” All pretty standard. But the list also included sexless pragmatic extras like forced air heating and municipal road maintenance, sewage and water, as well as a garage (preferably attached) and decent Internet and cellular reception.

In preparation, MacLennan and Harvey-Wickens drew up a list of potential areas and arranged to spend a weekend at each. Early on, they’d established what they wanted. But in time, what they didn’t want was also becoming clear. “We went up to Squamish several weekends in a row,” MacLennan recalls. Initially drawn to the area, they decided it wasn’t where they wanted to put down roots. “It’s interesting,” MacLennan says. “At the start of the weekend, you’d be, Oh, my gosh this is perfect for us! I love this place! And three days later, you’d be I’m over it. This is not for me, full-time.”

Midway through their search, though, they received some excellent news. In 2016 the couple became pregnant. This augured much, but it also threw shade on a particular type of property that, they decided, would now be categorically unfeasible.

It’ s perhaps the image that first comes to mind when you think of the archetypical BC getaway: a cabin perched on a high cliff, the expansive wrap-around deck with views of the Pacific, and oceanfront access via a precipitously winding, wooden staircase. It is the classic West Coast setting. And for small children, potentially dangerous.

A huge chunk of coastal BC was removed from their list.

Buying Patterns

MacLennen and Harvey-Wickens are younger than the demographic normally associated with vacation and recreational property buys. It’s tempting to extrapolate that they’re part of a trend, the vanguard of something exciting and new. Some sources imply that, in fact, they are. The 2018 Re/Max Recreational Property Report states that although the BC market is “driven primarily by retirees,” an “emerging trend” is the presence of “couples and young entrepreneurs…in search of work/life balance.”

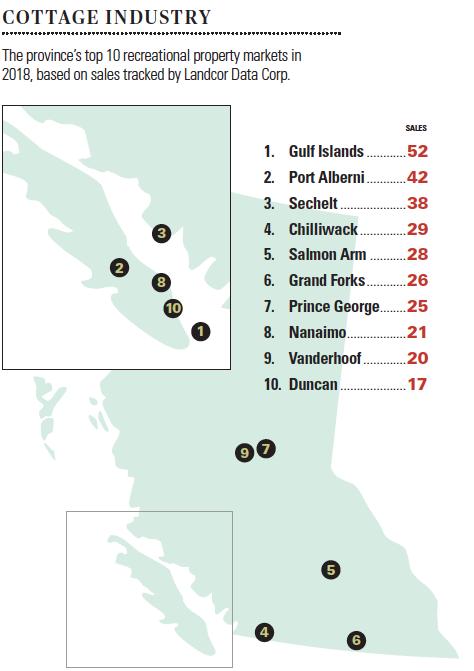

However, part of the problem with discussing trends in “vacation” home sales is that it’s not a distinct and trackable category. As of 2019, of the more than 2 million properties in BC – this total includes everything from farms and residential to industrial and commercial – about 54,789, or 2.65 per cent are designated “recreational” according to Landcor.

But the reality is that many homes used for vacation or recreational purposes – the ski-in condo at Sun Peaks or the waterfront bungalow overlooking Long Beach – are rolled into an amorphous Class 1 Residential designation. (Information acquired through the recent disclosure statements for the province’s new speculation and vacancy tax could paint a more complete picture. The results were still being compiled as of this writing.)

As you might expect, proximity dictates use: the closer a property is to major population centres, the more likely it will be used as a weekend getaway. And that, Rudy Nielsen says, is what many buyers want. “Get to your cabin on a Friday night, drive back on Sunday and still be at work on Monday morning,” he explains. “You’re what I call a Weekend Cowboy.” According to Nielsen, that’s one of eight categories that include everyone from the Private Island Buyer to the Apprehensive Buyer: convinced that the world is going to hell, the latter is looking for safe harbor – a mountaintop cattle ranch, for example, for when the cow dung hits the fan.

Others are in the game simply to make a buck: the potential for capital appreciation is a key driver for many recreational property investors. “Bear in mind that only 5 percent of the province is privately owned land; 95 percent belongs to the Crown,” Nielsen says. These investors are buying into a timeworn adage that has gotten more than a few speculators in serious trouble: Buy land; they’re not making any more of it.

Where are they buying? The traditional hot spots – from the Gulf Islands and Qualicum Beach to the North and South Okanagan – are still in play. Overall, ski resorts have tended to hold their own, with non-resident owners a factor in at least some destinations: at 17-percents non-resident ownership levels, Sun Peaks tops that list (Whistler is close behind at 16 percent). Some regions grabbed headlines: “Tofino Values up by 112%!” was one of the more eyebrow raising claims from mid-2018. (It’s an alarming statistic, until you realize that if reflected the value of waterfront sales only, and that there were a dearth of those particular properties on the market the previous year.) But, overall, according to Re/Max, the vacation home market is considered favourable to sellers – despite the initial handwringing over the speculation and vacancy tax.

The initial rollout of the tax was hardly textbook. The ensuing backlash eventually caused Finance Minister Carole James to rethink it and change course; today, the spec tax affects mainly urban areas where housing values have spiked, sparing most of the vacation property inventory form the additional levy.

Still, there was the fear that buyers would avoid places where the tax was in forces, choosing to look to other communities outside those zones. This didn’t happen to any great degree, though. “The spec tax is probably hurting sales in some communities,” concedes Brendon Ogmundson, deputy chief economist with the Vancouver-based British Columbia Real Estate Association. “But it doesn’t seem to be making a huge difference when you do community-to-community associations.”

To illustrate, Ogmundson cites two areas where the tax is differentially applied. “Parksville-Qualicum, where there is no spec tax, is performing about the same as Nanaimo; in fact, Nanaimo sales are trending up a little bit, whereas Parksville-Qualicum is flatlining.” A similar situation exists in the Okanagan. In areas affected by the new tax, sales have dropped 32 percent. But in the southern Okanagan, where the tax isn’t part of the equation, sales have fallen, even more precipitously, by about 45 percent.

There are several variables in play, from the downturning Albertan economy to a growing feeling that BC’s housing market is overpriced. But availability of credit may be the most significant factor. “The overall theme in all the data is that we have the B-20 stress test happening, which affects all markets, swamping all other trends,” Ogmundson says.

Financing a vacation home can present its’ own, unique hurdles. Even for those who come armed with a pre-approved mortgage, financing a purchase in some regions can be difficult. If you’re looking to buy in, say, Whistler or the Okanagan, there’s usually no problem, since there are several valuation tools to assess property prices and ensure that a lender’s exposure risk remains in acceptable parameters.

But once a buyer starts looking further afield, the process becomes more complex, says Vancouver-based Rob Regan-Pollock, vice-president of the BC chapter of the Canadian Mortgage Brokers Association. “A cottage on a lake in the middle of nowhere: that’s when the lenders start applying different criteria,” he says, adding that for many of these properties, a 35 percent minimum down payment is not uncommon. And you’ll likely be on the hook for a bank-approved appraiser to travel to the site, too.

That’s not all. You’ll also have to satisfy lender concerns about water potability and the state of the septic system. And you might want to avoid any dwellings that aren’t built on concrete. “If it’s a non-continuous foundation, or a wood and block foundations, lenders are typically not interested,” Regan-Pollock says. “They want to make sure the economic life of a particular building is going to exceed amortization by five years.”

And for those that fall in love with an unserviced lot in a remote location? “If the lot is not serviced, there are very few lenders that will actually lend on that type of land,” Regan-Pollock explains. “The ones that do, institutionally, usually require 50 percent down.” And, he adds, collateral in the form of a more easily traded urban property – like your principal residence.

Trouble in Paradise

Ultimately,as it with so many real estate purchases, when it comes to buying a vacation property, emotion is the primary driver, overwhelming rationale and snapping best-laid plans like driftwood. It’s the power of the dream, of course.

For some, the dream will come with unanticipated costs. British Columbians whose long-term goal is toe eventually transition to their place in the country (while keeping their family home in the Lower Mainland, Victoria, or Nanaimo, for example) will have to factor the speculation and vacancy tax into their retirement plans. If they spend more than six months in paradise, they could be forced to rent out their family homes, or pay the tax – more significantly, their principal residence tax exemption will then be on the line too.

And for those who buy property with an eye to eventually selling it to finance their golden years? A cabin is not a shoebox full of Apple shares. It can take a long time to shift a rural property. As an asset class, recreational property is hardly liquid.

Then there’s the health-care wild card, something often lost in the excitement of the purchase, especially if buyers are younger. Hospitals in urban centres are better equipped to deal with a wider range of emergencies and significant health issues than their rural counterparts. If your Plan B includes downsizing to the countryside, this may not end up being trivial.

But again, once your mind is made up to buy a vacation property, it’s often emotion- the wallowing kick to your amygdala that occurs when destiny and possibility collide – that will be the deciding factor. Even for those who, like Kate MacLennan and Alex Harvey-Wickens, treat the search largely as an exercise of reason over passion.

In the end, though, the couple got almost all of what they wanted. Waterfront? Check. Fireplace? Check. All the sexy stuff, like municipal sewage, water and road maintenance? (Oh, baby.) The only thing on which they really compromised was location. Purchased in November 2018, their new place is farther away from where they were first looking.

About 4,500 kilometers farther, actually.

You can’t drive there, not easily. But really, taking a flight from Vancouver to Toronto’s Pearson International Airport, coupled with a two-hour drive to Ontario’s cottage country, is only marginally longer than the Vancouver-Tofino commute.

They plan on going as often as they can. Weekends are out.

Telephone: 604-606-7900 | Email: [email protected]

Copyright © 2012 Niho Land & Cattle Company. All rights reserved. | Privacy Policy | Terms of Use | Webmaster