North Shore real estate: The new gold rush

Jane Seyd, North Shore News, May 7, 2016

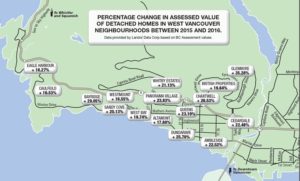

[caption id="attachment_17790" align="alignleft" width="341"] A map showing the changes in assessed values of single-family homes between 2015 and 2016 in West Vancouver neighbourhoods, using data provided by Landcor Data Corp. and BC Assessment. graphic Myra Mcgrath, North Shore News[/caption]

A map showing the changes in assessed values of single-family homes between 2015 and 2016 in West Vancouver neighbourhoods, using data provided by Landcor Data Corp. and BC Assessment. graphic Myra Mcgrath, North Shore News[/caption]

For the past 13 years, freelance writer Alex Rose and his family have lived in a neighbourhood of gentle green hills in West Vancouver, on the corner of St. Denis and Palmerston. Rhododendrons and roses bloom in gardens and there’s a view across Burrard Inlet from the deck.

“It’s a very modest house with a lovely bit of land,” said Rose – similar to other older homes that used to make up the neighbourhood.

But in the past two years, as house prices surged, things started changing. “All of a sudden there was a huge uptick” of houses being bought and sold.

“Eighty per cent of our street has been sold,” said Rose. “The last couple of months have really been madness.”

Real estate is the new gold rush on the North Shore, where dramatic increases in property values are creating winners, losers and big changes.

Property assessment notices that came out in January 2016 – showing the value of properties in July 2015 – confirmed what most already knew. Values for typical single-family homes were up 15 to 25 per cent in the past year – on top of dramatic gains the year before.

“You would have to go back to 1980 to find only two or three times that assessments have moved this much, this quickly,” said area assessor Jason Grant of the BC Assessment Authority.

In this white-hot market, owners of an average home in Lynnmour – a neighbourhood of older, modest houses near to an industrial area and the Ironworkers bridge – were now members of the million-dollar club. Assessments in West Vancouver’s Bayridge neighbourhood shot up 29 per cent while Glenmore was up 35 percent. Homes in Pemberton Heights, Delbrook and Edgemont all rocketed up more than 20 per cent.

Since those assessments – which now lag 10 months behind the market – came out, property values have only continued to climb. A buying frenzy across the Lower Mainland this spring resulted in a record month for sales in greater Vancouver in March. Last month also saw a record number of sales for the month of April.

According to statistics from the Real Estate Board of Greater Vancouver, the benchmark price for a single-family home in North Vancouver is now a little less than $1.5 million, up more than 30 per cent in one year and up more than 65 per cent from five years ago. In West Vancouver, the benchmark price of a detached home is now $2.9 million – up more than 31 per cent since the same time last year and more than 75 per cent in five years.

“It boggles the mind how expensive it is,” said Allan Angell, who has been selling real estate at the top end of the West Vancouver market for more than 40 years.

A decade ago, houses that sold for more than $5 million were still relatively rare on the North Shore. In 2004, for instance, only five of those were sold in West Vancouver, said Angell. This year, there were already 83 homes sold in that category between January and mid-April.

“The land cost in North and West Vancouver has escalated on an exponential basis over the past eight months,” said Jason Soprovich, another West Vancouver real estate agent who specializes in the luxury market.

“We’re seeing parcels of land that a year ago sold for $2.5 million that are now selling for $5 million,” said Soprovich. “I mean a piece of property that has an old-timer on it you can tear down. That is extreme. It’s happening in Edgemont Village. It’s happening in Altamont and throughout the West Vancouver corridor.”

The frenzy among buyers has prompted bidding wars at all levels of the market. At the high end, Soprovich listed two properties in the coveted 2800 block of Bellevue Avenue recently and received multiple offers on both. One of those, listed for $11.5 million, ended up selling for $12.5 million, making it the most expensive piece of real estate sold in the first three months of 2016 in West Vancouver.

A modest house in the 1100 block of Haywood Avenue – which will likely be torn down – was listed for a little less than $3 million and received at least 10 offers, eventually selling for almost $3.7 million.

Conditions that include low interest rates, high demand and an influx of wealthy immigrants have created what Soprovich describes as “a perfect storm” in the real estate market.

A new house on Hillcrest Street, in the Westmount neighbourhood, offers a glimpse of what those at the high end of the market are looking at – a gleaming six-bedroom, seven-bathroom, 6,000-square-foot home in tones of white and grey, listed for sale at slightly less than $7.5 million. There’s a pool, nanny’s quarters, wet bar and projector screen entertainment system, along with marble finishes, hardwood floors, a separate wok kitchen and expansive views out towards Lions Gate Bridge.

The old house on the property – a well maintained home from the 1950s – was torn down by the builder who bought it to make way for the new one with more market appeal. The luxury spec house was built in 14 months, said Soprovich, and the builder is hoping for a relatively fast sale.

Next door, an excavator gnaws at the ground as contractors begin work on the neighbours’ new home. Soprovich sold that property to a couple from Whistler three years ago. But the older house on the property “wasn’t quite what they were looking for,” he said. So the construction cycle is starting again.

For the most part, who is buying homes at the top end of the market is not a mystery.

Both Realtors and academics who have studied the issue say international investors make up about 70 per cent of buyers. On the North Shore, most of that money is coming from Mainland China.

“I take it as a given that foreign capital is driving the top end of the market,” said David Ley, a University of British Columbia geography professor who has spent 15 years studying immigration flows between Asia and Canada.

In the case of those Ley calls “millionaire migrants,” there has been a consistent association with property investment.

Until very recently, the province has not kept any statistics – or at least acknowledged doing so – about who buys property. At times, the real estate industry has also disputed the influence of foreign buyers on the market.

Ley said there are reasons for both to downplay the influence of foreign capital in the housing market. “Some members of the development lobby don’t want to harm the goose that lays the golden egg,” he said. The province has also benefited through collection of property transfer taxes, he said – estimated at more than $1 billion in the last fiscal year.

“The market is on such a tear the development lobby is benefitting immensely and the development lobby is an important funder of politicians in this province,” said Ley.

But Ley said three studies that have looked at the issue – two academic and one done by Macdonald Realty – all concluded, “the top end of the market is dominated by buyers from China.”

The effect of that “does trickle down,” he added.

Allan Angell said the change in buyers has been noticeable in the past five years.

Angell keeps track of who’s buying what in the West Vancouver market.

He scrolls down a list of statistics he’s compiled that show the vast majority of sales more than $2 million in West Vancouver have been through real estate agents on the buyers’ side who cater almost exclusively to buyers from Mainland China.

In March, Angell decided to examine land title information on about 350 homes on four streets in the British Properties – a neighbourhood once infamous for a historical covenant that forbid the sale of properties to people of Asian or African descent.

Angell found about 70 per cent of those owners had ethnically Chinese names.

When urban planning researcher Andy Yan did a similar examination of land title records for three high-end Vancouver neighbourhoods it prompted some accusations of racism.

Ley called that “a tactic to limit discussion.”

Those who are looking at the issue say such crude instruments are all that’s available in the absence of hard data on foreign buyers and the influence of foreign capital.

That’s something both academics and politicians have called for.

“We need some senior government leadership,” said West Vancouver Mayor Mike Smith. “To say you haven’t got evidence of who’s buying is just passing the buck. They don’t want evidence because they don’t know what action they should take.”

Much about the North Shore, and West Vancouver in particular, appeals to foreign investors, particularly buyers from China.

“Predominantly they like larger parcels of land. They like views. They like new. And they like big,” said Soprovich, adding it’s not uncommon for multiple generations of a family to live together in one larger home.

Families are also looking to have their children go to the best schools, he added, and will sometimes buy based on a school’s catchment area.

That’s borne out by statistics from the West Vancouver School District, where the number of English Language Learner students has more than doubled since 2009 to more than 1,000 students – or about one in seven. The dominant first language for those students has also switched from Farsi to Mandarin.

Soprovich acknowledges the growing influx of wealthy immigrant buyers is “a sensitive issue. There’s always a bit of blowback when the market is a hot environment.”

“We all have to understand we’re an evolving city and it’s going to continue to change in the years to come.”

Regardless of who’s buying, Smith worries about the effects of skyrocketing real estate values. “It’s dividing the community,” he said. “If you’re a property owner, you’re pretty happy, particularly if you were planning on selling.”

But younger people who grew up in West Vancouver and have family and friends and even well-paying jobs here are increasingly frustrated at their lack of housing options, he added.

“It’s created division between the winners in this thing who are the current homeowners and the people who are not winners.”

Even some of the winners are questioning the rapid pace of change.

Craig Cameron, a West Vancouver councillor, lives in an Ambleside neighbourhood about a block from municipal hall on a street where people still know each other and get together for a block party every year.

When family friends moved in down the street, Cameron said he was happy that his kids would have their friends nearby.

But recently that family – like so many others – put their house on the market.

“What’s going to happen now?” he said. “Are we going to have a situation where we have a house that’s empty? What if somebody buys it and knocks it down?”

People in Cameron’s neighbourhood – like many on the North Shore – have grown used to door knocking by real estate agents and their property scouts.

Recently his wife opened the door to two young women representing real estate interests who told her once again about the opportunities to sell, adding, “We’re having a real shortage of inventory.”

Cameron said he’s bothered by that concept of housing: “It’s just a commodity like lumber or gold or a barrel of oil. It’s just a way to make money. Or a place to park money. To me that is not what homes are.”

Cameron said he fears the day when three-quarters of the neighbours no longer show up to the block party “because they’re just here for a short time. Or they’re not even here.”

Cameron disagrees with those who argue the market should be allowed to operate without government intervention.

“We don’t have to be totally passive in the face of change,” he said.

“This market is not being created domestically. It’s being goosed by foreign investment. You have to examine what foreign investments are doing and whether it is good for a community perspective overall.”

Various suggestions have been put forward in the past year for ways to cool the housing market and to limit both foreign investment and speculation in it.

Some jurisdictions in other parts of the world don’t allow non-citizens to buy certain types of housing or place limits on that. Others levy hefty taxes on foreign capital entering the real estate market. Additional taxes on speculators who rapidly flip property and on purchases at the top end of the market have also been suggested.

But so far, “British Columbia has none of these things,” said David Ebey, the NDP critic for housing, who has often lambasted the provincial government about inaction on the topic.

“I’m blown away that B.C. and Canada seem to be the only jurisdictions who are not taking the issue seriously.”

Such measures could have an impact, said Ley.

“In my perception, price increases enter the market through the top end and trickle outwards into lower priced areas,” he said. “If you can stop the rapid increase at the top, that’s a helpful thing to do.”

But not everyone – particularly in government – thinks that is a good idea.

“I don’t think the government’s planning to do anything to pull the rug out from under these prices,” said Ralph Sultan, MLA for West Vancouver - Capilano.

“One’s home is typically the biggest asset anybody has,” he said, adding government interferes with that value at its peril.

“Anything the government does is probably going to have an adverse financial impact on a lot of people and these people are constituents and they are voters.”

Cameron finds that argument disheartening. “What you’re saying is ‘I won the lottery. Don’t mess with my lottery winnings.’”

Real estate is also big business, particularly on the North Shore.

According to statistics from the Real Estate Board of Greater Vancouver, the total dollar value of real estate changing hands tripled in West Vancouver over the past decade, from less than $1.2 billion in 2005 to nearly $3.6 billion in 2015. North Vancouver wasn’t far behind, jumping from less than $1.4 billion in total sales in 2005 to more than $3 billion in 2015. This year, $1.5 billion worth of property changed hands in real estate transactions between January and March alone in West Vancouver, with $1 billion in total sales in North Vancouver.

According to the Real Estate Council, a total of 1,381 real estate agents are licensed to brokerages on the North Shore.

All of which makes government reluctant to turn off the tap, said Cameron.

“Why do you think B.C.’s not in a recession? You’ve got Realtors making millions. You’ve got lawyers and accountants and big construction companies making hand-over-fist money,” he said. “They’re making more than neurosurgeons.”

It’s a market where cashing out has become a serious consideration for many homeowners.

Alex Rose is one of them.

He and his wife used to ignore the knocks of Realtors on the door. But as the prices climbed higher “we began to have some fairly serious talks,” he said.

As a freelance writer, “I never got myself a pension,” he said. So when opportunity came knocking recently, he answered it.

Their house sold in 48 hours, without ever going to multiple listing.

Real estate documents show the property, which the family bought for $870,000 in 2003, sold for $3.75 million – $750,000 over the list price and $1.28 million over the assessed value.

They move out at the end of June.

Rose and his family are putting money away for retirement and moving to Caulfeild, where they bought a house after being outbid on two other properties. In one case, “a man came along one weekend and just wrote out a cheque,” he said.

Rose said he has no illusions about what will likely become of his home on St. Denis and doesn’t feel bad about it.

“A family has to decide what is right for it,” he said.

The recent real estate boom has shown you just never know. “You might think (your neighbours) are the ones who are never going to go. Then one day the sign’s up and a week later it says sold,” he said.

“People do change their minds. Especially in the face of big money.”

Telephone: 604-606-7900 | Email: [email protected]

Copyright © 2012 Niho Land & Cattle Company. All rights reserved. | Privacy Policy | Terms of Use | Webmaster